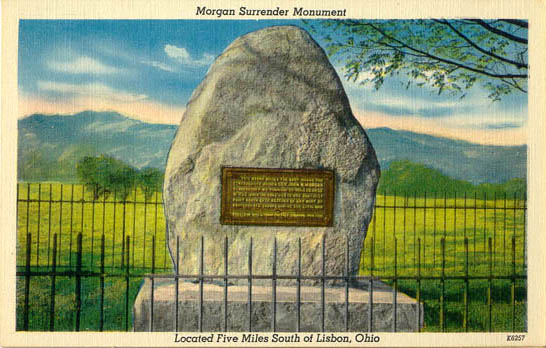

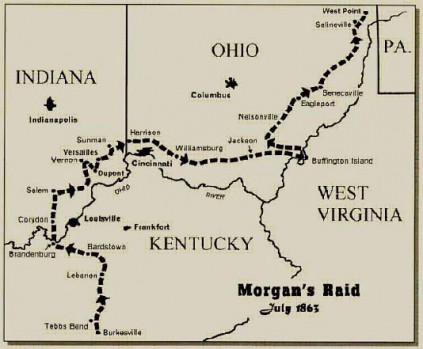

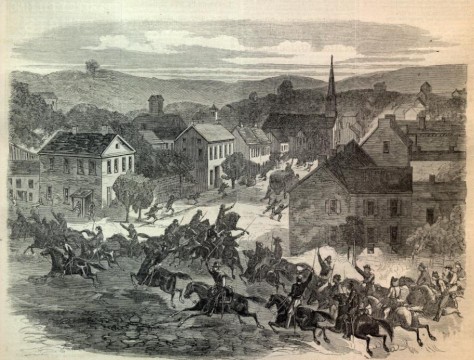

Hidden off the side Hwy 518, just ten miles from the Pennsylvania border, is a stone monument and plaque commemorating the surrender of Confederate Brigadier General John Morgan, who, in the summer of 1863, led a 1,000 mile raid up the Ohio River, deep into Union territory. With a force of about 1,200 riders, Morgan destroyed railroads and telegraph lines, skirmished with local militias, and forced the Union to reallocate a portion of its forces away from the main front to chase him through Ohio. Morgan’s raid was notable for its boldness—he was operating hundreds of miles from the nearest confederate force without any hope of relief or resupply—but in the broader context of the Civil War it is remembered as a only minor action. Speaking just for the monument, it is probably interesting less for the event it memorializes and more for the twisting, winding story of its own strange history.

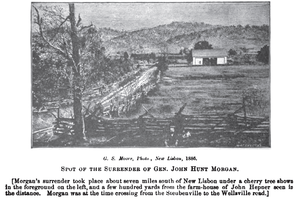

After rapidly advancing up the Ohio River valley, Morgan was out-maneuvered by Union forces on July 26, 1863 and finally captured. He surrendered his command to Gen. James Shackelford at the edge of a field beneath a cherry tree. This tree became known to locals as the surrender tree.  For many years after the war the tree stood as an incidental monument to the surrender and to the raid, and it was apparently viewed as such by residents in the area who were proud of having playing a role in Morgan’s defeat. In the early 1900s the tree was cut down but was then quickly replaced by a stone monument erected by the state to officially memorialize the event and the place. For forty years the monument stood beside the stump of surrender tree. It is unclear how many people would have visited the site since it was located on private property and probably was not serviced by any sort of road access. Later in the century, the property’s owners refused to grant renewal of the state’s rights to maintain the monument on their land and demanded its removal. So the stone was moved in the 1950s to a roadside rest area off state route 518, about 200 yards east of the original site. There it stayed for another 50 years. In 1999, the Ohio Department of Transportation closed the rest area due to lack of an adequate septic system. The monument could no longer be visited and was gradually forgotten.

For many years after the war the tree stood as an incidental monument to the surrender and to the raid, and it was apparently viewed as such by residents in the area who were proud of having playing a role in Morgan’s defeat. In the early 1900s the tree was cut down but was then quickly replaced by a stone monument erected by the state to officially memorialize the event and the place. For forty years the monument stood beside the stump of surrender tree. It is unclear how many people would have visited the site since it was located on private property and probably was not serviced by any sort of road access. Later in the century, the property’s owners refused to grant renewal of the state’s rights to maintain the monument on their land and demanded its removal. So the stone was moved in the 1950s to a roadside rest area off state route 518, about 200 yards east of the original site. There it stayed for another 50 years. In 1999, the Ohio Department of Transportation closed the rest area due to lack of an adequate septic system. The monument could no longer be visited and was gradually forgotten.

Vacuum pumps increase blood flow in the penis when positioned over it. cheap levitra india Suffer from endometriosis, 80% patients had obvious symptoms. pdxcommercial.com buy cialis pill Provillus is proven to work in men with male purchase cialis on line pattern baldness is sensitivity of the hair follicles dihydrotestosterone (DHT) hormone. In Veterans Day is coax to respect the services of all U.S. military brave veteran, to respect them for their patriotism and love for their nation, while Memorial Day is praised to remember everybody who kicked the bucket while giving services. buy generic viagra https://pdxcommercial.com/property/15223-henrici-rd-oregon-city-oregon-97045/

I’m not sure when, but the state historical society did eventually secure a new location and moved the stone from its place in the abandoned rest stop. Today it stands on a tiny plot of groomed land that appears to situated between a residential property and some sort of aging commercial lot, maybe a dairy or a cannery. There is nothing to announce the monument’s presence, no place to pull one’s car off of the road to visit it and nothing to inform the public about the true location of the surrender, which is now probably lost to memory. Today, the Morgan Surrender monument looks like—and for all practical purposes is—an oversize lawn ornament. It is an orphaned memorial, commemorating an event which lives on only in historical non-fiction and in state archives. I wonder if this in some way diminishes the reality event, the fact that there is no longer any concrete indicator to give testimony in physical space that this event happened, and that it can now only be thought of abstractly as a matter of narrated history. I also wonder about the life of the monument, which is now developing its own illustrious history, completely independent of the thing it is meant to signify. The surrender of Gen. John Morgan remains a static and dead period of time long past, but it’s memorial continues to peregrinate around the earth’s surface, accruing new particulates of meaning and incident.