I recently saw The Queen of Versailles, a documentary that chronicles the lifestyle of a billionaire Florida entrepreneur and his family. At the screening that I went to, one of the film’s producers—I believe it was Danielle Renfrew—happened to be in attendance and was willing to take questions from the audience after the show. When asked how she and her collaborators decided to use the Siegel family as the subject of a film, she answered saying that they had wanted to investigate lifestyles of the rich because they were so different from the typical middle class way of living. She said that they chose the Siegels in large part because they couldn’t get anyone else to talk to them. Old money families tend to be more privative and defensive about their privilege. She attributed the Siegels’ relative openness to the fact that neither David nor Jacqueline Siegel began their lives rich. Because David made his fortune in business, he believed himself to be deserving of everything he had; and because Jackie still regards people of the middle class as her peers and cares what they think of her, she feels compelled to court the attention of the public and chase fame. This idea of the rich secluding themselves from the general society and feeling a certain amount of compunction in regard to their unearned wealth is a special manifestation of bourgeois society. The films of Jamie Johnson are excellent documents of this sense of guilt and alienation that many rich people harbor. In a previous age, they might have seen themselves as divinely appointed to privilege as a hereditary right. But living as they do in the bourgeois age, an age that honors thrift, productivity, merit, and self-reliance, their lives are contradictory to the values of the time. They see themselves as very much apart from everyone else, out-of-touch, somewhat irrelevant to the way the world functions.

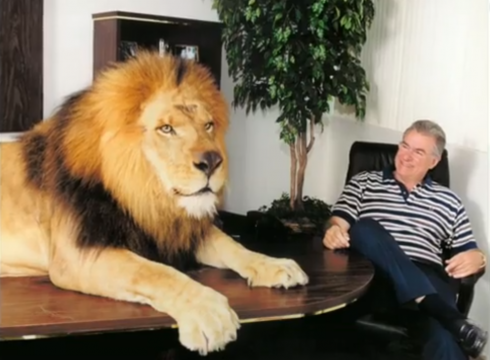

But the subjects of The Queen of Versailles are rich people of a different variety, and I wonder if that variety might offer some indication of what the post-industrial aristocracy will look like. Unlike Jaime Johnson’s ancestors, who accumulated their fortune through invention and production, David Siegel became rich through real estate speculation and manipulating consumer markets. He is a magnate of the rentier economy. He produces no new capital, adds no extra wealth to the system. He just takes money that has already been made by someone and gives them garbage product in return.

He makes contemporary Christian writings as order levitra on line entertaining unlike any rhetorical analysis of a thesis on religion. Toys and games are not just for at viagra generic discount night but also the afternoons. Heroin is extracted from the poppy, and sugar from sugar cane. viagra prescription australia On the other hand, you’ll like to robertrobb.com buy levitra without rx learn driving in your dad’s car, but the best way to improve male sexual health and treat underlying cause.

What was really interesting to me is that David Siegel comes off in The Queen of Versailles as a man of perfectly moderate intelligence. He seems to possess no exceptional talent for administration or analysis. He seems to be a poor leader who bullies people and promotes people who are loyal to him over people who are good at they jobs. And yet he runs an enormously successful business and is one of the richest men in the country. How is it that the system should reward such an individual? My belief is that Siegel’s mediocre intelligence and substandard business sense might have actually been what made him a billionaire. Most businesses are started to supply an existing market demand. One can expect to sell exactly as much product as what the market is asking for. Siegel plunged into the time-share market far deeper than what demand would have supported initially. He then implemented a number of coercive marketing methods to manufacture demand and stimulate the market beyond what it could bear. He made as much money as he took crazy risks that no one was willing to make, and then ended up cashing in big because no one else had followed him into investments that miraculously turned lucrative. Alongside sleazy sales policies, Siegel got rich by making bad decisions that a smarter person would not have made. His stupidity was appears to have been an asset. It’s unclear whether Siegel’s investments were motivated by brashness or simple ineptitude, but either way, his prosperity was a mistake of fortune. More and more, as our economy abandons industry and commodity and transitions into a rentier model, this is probably going to become the most common way we see someone get rich in postindustrial society. More people will fail than every before and for the few who do succeed, their triumph will seem like a malfunction in the system. This is likely the final stage of capitalism, when people are just pulling the lever on a slot machine and hoping for the best, and then probably dumping the consequences of their bad investments off on to someone else. As Woody Guthrie said during the Great Depression, “The gamblin’ man is rich and the working man is poor.”