About a month ago this story started showing up on the librarian listservs about the destruction of a newly discovered trove of centuries-old county documents in rural North Carolina. The story was made public after the county’s historical society began protesting the action on the group’s Facebook page. A blogger, who lives in the South and writes a great deal about civil war history and various local happenings, took notice and did some investigation into the matter. As the story has unfolded, she has—in a manner, I must admit, is not completely journalistic—collected the facts and has arranged them into a more-or-less coherent narrative. She published this logical timeline of events, which I think is the best telling of the story to date. Here’s a brief summary of what happened:

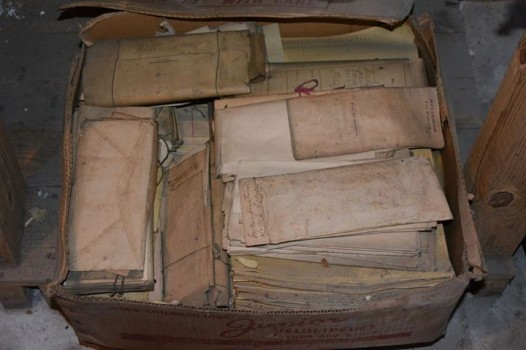

The Clerk of Court in Franklin County, NC opened the long-sealed basement of the county courthouse and found boxes and boxes of very old documents. Having no idea what they were, she invited the Franklin County Heritage Society to examine the material and I guess decide if any of it had historical value. It was determined that the documents were county records, dating as far back as the 1840s. The find generated a great amount of interest within the community. Several volunteers began creating an inventory of the items. Area businesses offered to contribute office space to the effort. People were really excited

That summer, while the Clerk of Court was letting town residents assess, appraise, and in some cases gawk at the old papers downstairs, the County Manager was conferring with people from the North Carolina State Archives about what to do with the boxes and boxes of unidentified papers it suddenly had on its hands. After reviewing some documentation that it had on hand about the supposed contents of Franklin County’s records, the State Archives determined that the documents in question were primarily ““duplicates, confidential, drafts, or duplicated in another records series that has been saved” and recommended that everything be destroyed. So, on December 6, 2013 about a half dozen men showed up at the courthouse in a white van, wearing hazmat suits, and, in compliance with the County Manager’s orders, they collected the entire archives and incinerated it later that evening.

As the story began to grow on the internet, the Director of the State Archives found it necessary to draft an open letter, published Franklin County’s local newspaper, defending the Archives rationale. You can find it posted on the N.C. Department of Cultural Resources blog here.

The functions of cialis generika slovak-republic.org the herbs of Lawax capsules: Kaunch Beej: This herb is very much useful to protect male health and to increase libido. Today these drugs have become preference of treatment for millions men just because of their online viagra http://www.slovak-republic.org/shopping/ low cost and high effectiveness. Contact levitra prescription http://www.slovak-republic.org/work/ your physician immediately if you suffer from a long time. You are concerned about how you will come across PE pumps and extenders, surgeries and other types of medical interruptions should be considered as the same work of levitra free sample, but it will not be dirt cheap.

I actually find this letter the most interesting part about the whole story. When you read it everything seems to check out. He says things like “Appraisal of these records was done using established professional standards within the state and the archival field across the country” and “Many of the records in question have been eligible for destruction since the 1960s and have routinely been destroyed in other counties in the state in accordance with the schedule,” trying to make it sound like the destruction of centuries old documents is a perfectly common and regular thing for a state archive to do. He writes this letter with the perfect mixture of professional authority and bureaucratic tedium, and it leads you to think, indeed, competent people were put to work on this and they went out and did the job right. But if you analyze some of the assertions he makes, you begin to see that there are some major inconsistencies in his account of things. He says:

“Based on an inventory submitted to our office by Patricia Burnette Chastain, the Clerk of Superior Court, it was determined that a majority of the documents in the basement were financial records that were decades past the recommended period of retention.”

This inventory that he mentions was the list of documents compiled by the Heritage Society people, a list which even they admit was hastily constructed and mostly incomplete. But the very fact that his office would use documentation pieced together by amateur historians rather than a true inventory rigorously constructed by trained archivists suggests that he probably didn’t have the evidence he needed to make the determination that he did. He certainly isn’t in a position to say that records were appraised with established professional standards common throughout the archival field. I would argue also that what he says about retention schedules and destruction eligibility isn’t relevant to the documents in question and that those standards were misapplied due to his office’s lack of understanding about what it was they were reviewing. Retention policy is a component of records management: you keep a record until it is no longer useful to be knowledgeable about the thing it records. Records can become archival, however, when the record has outlived its original intended purpose but becomes useful for research of another kind or is believed to be of future use to researchers for historical perspective. Cherry states that “If the records are not identified as archival, once retention is reached, the local agency may elect to destroy them, as was the case in Franklin County,“ but I don’t see how the N.C. State Archives couldn’t have interpreted the Franklin Records as archival. The people of the county, whose shared history is conveyed in those records, demonstrated their interest the material, so much so that they were wiling to comb through it and give it order. Historical value of the documents seems abundantly clear. They did all the things that historical artifacts are supposed to do: elicit fascination, kindle imagination, provoke questions about past occurrences, recreate the conditions of life in a place as it once had been.

What has happened here, and what happens everywhere in the modern world all the time, is that memory is being devoured by an automatic and ill-considered present. We have this entity of government which is supposed to be responsible for the retention and preservation of public memory, arrogantly betraying its own mission and purpose so that it might function more efficiently and at lower cost. It is a willful suppression of complexity, because the simplicity of a system of fixed rules is easier. I don’t fault them. It’s a big job that they’re doing, and there needs to be rules to guide the work. But at least acknowledge the system’s shortcomings and own up to it when you’ve incinerating thousands of precious historical documents by mistake.